- No products in the cart.

Opening:05 Abr, 2018

Professional visitors:05 Abr, 2018

Opening to public:05 Abr, 2018

Share:

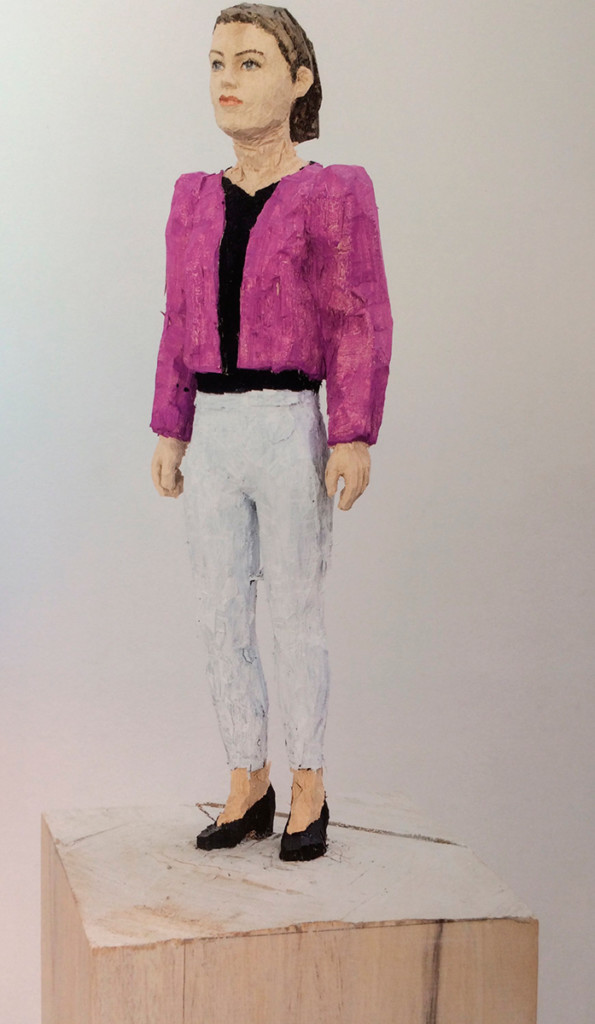

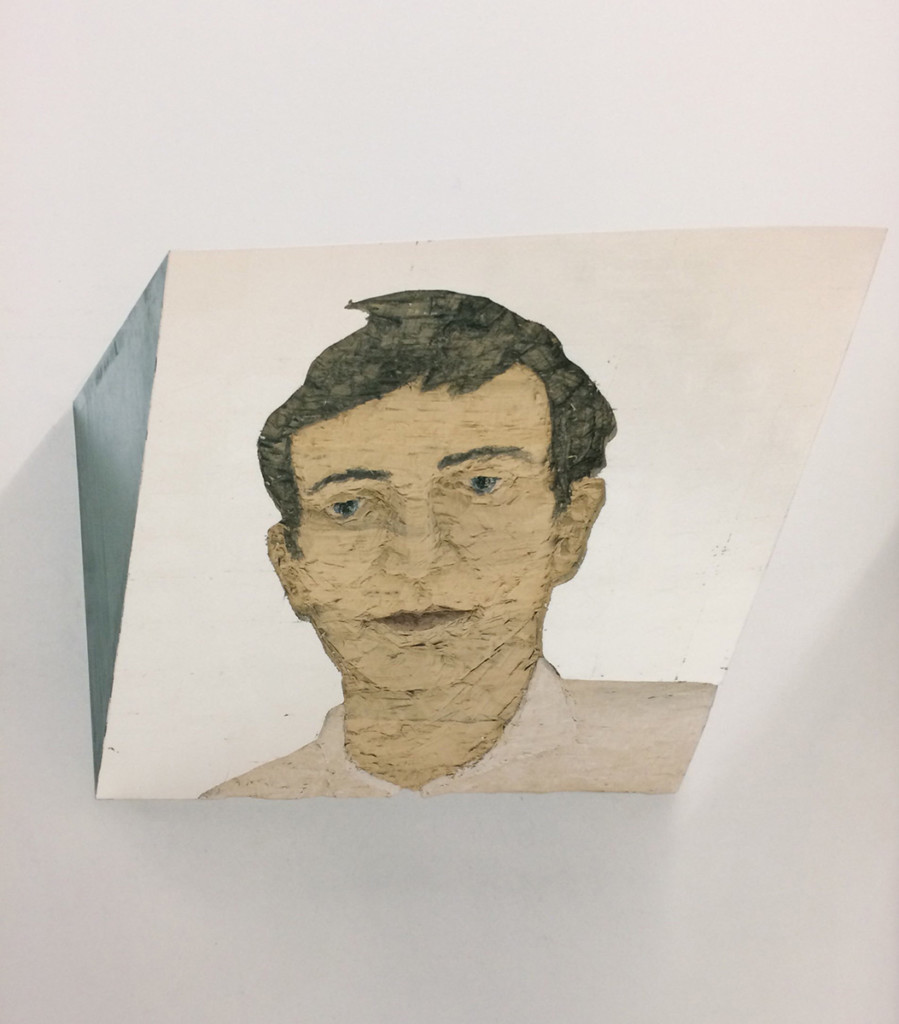

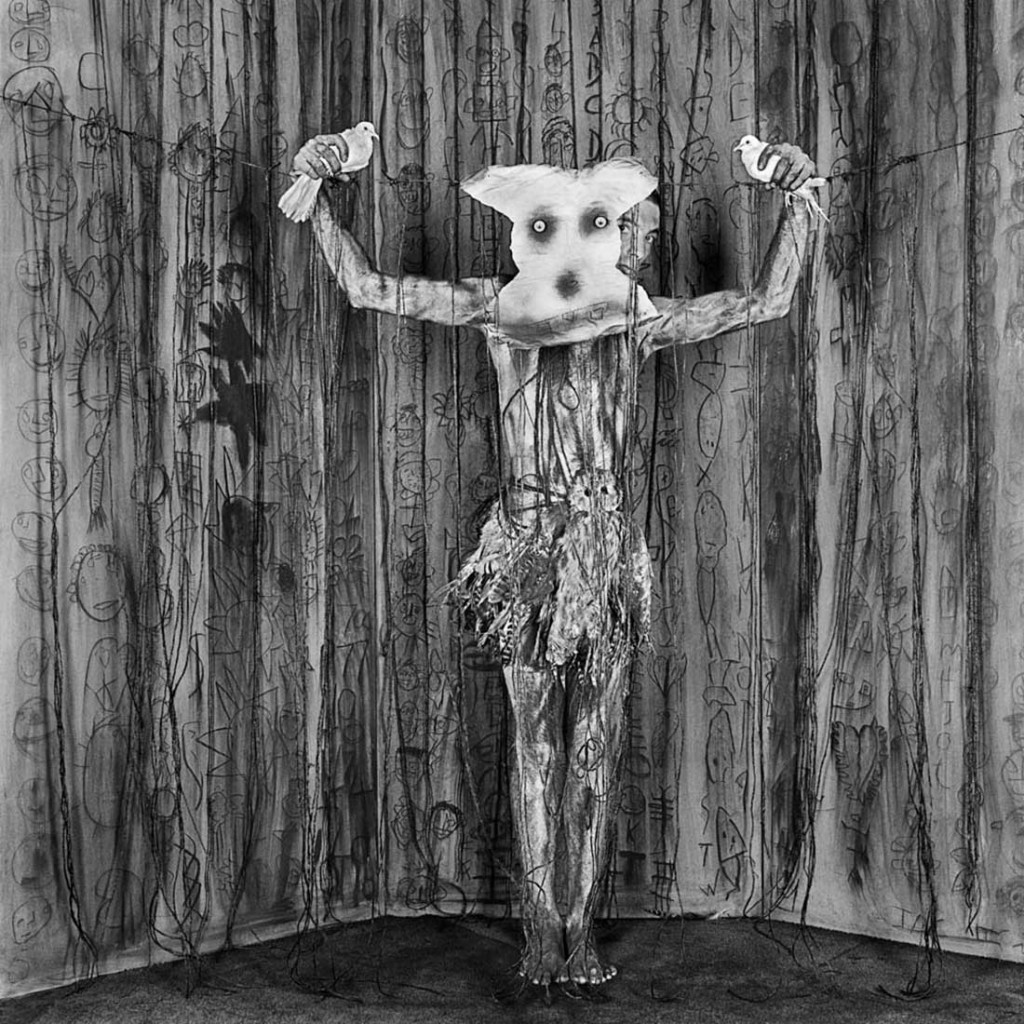

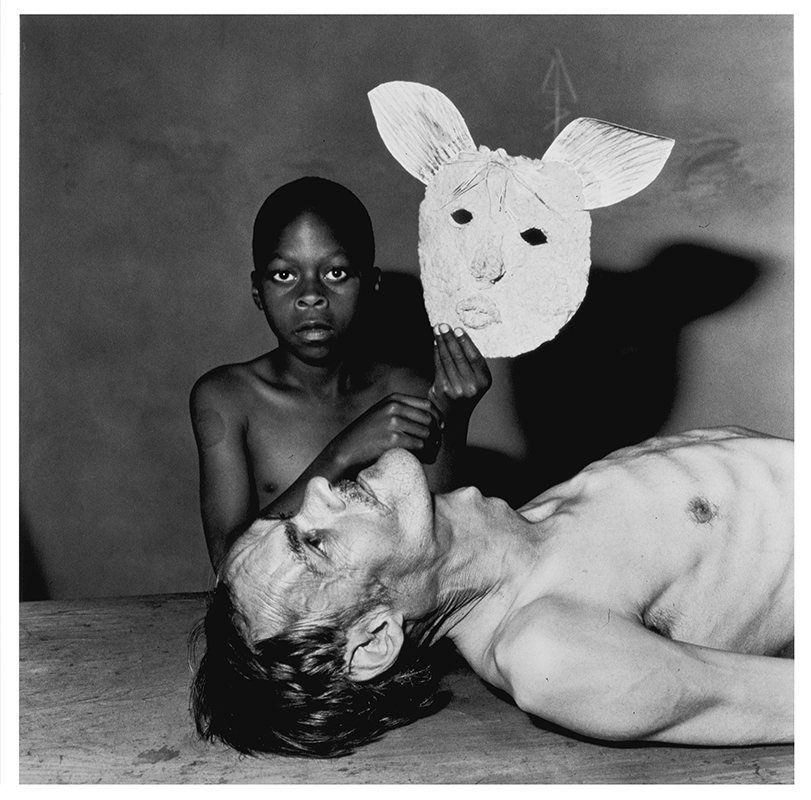

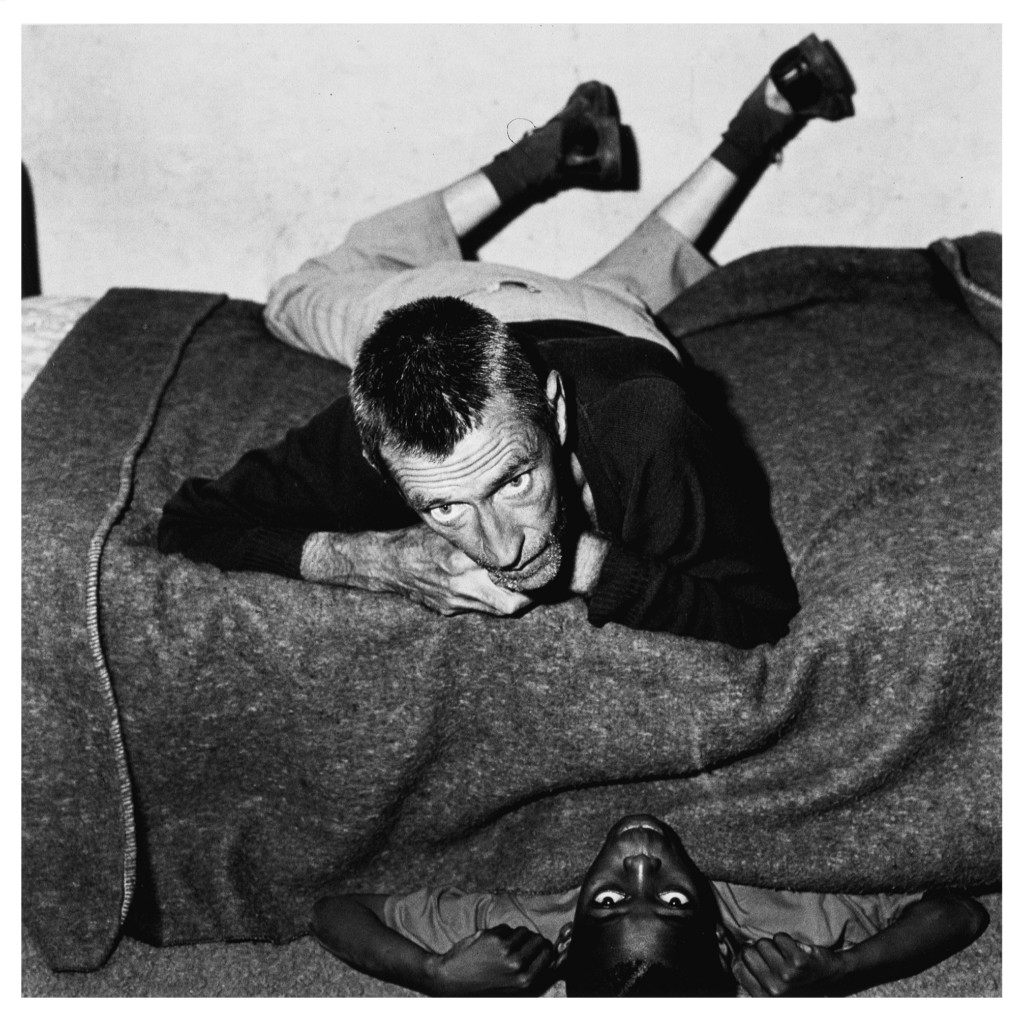

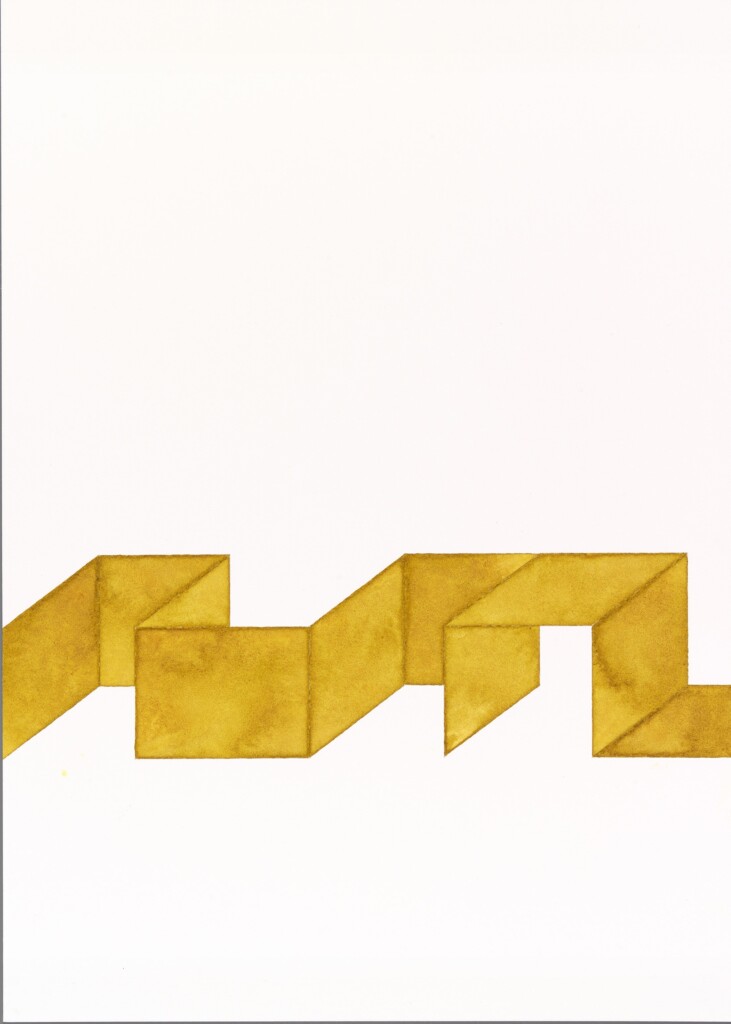

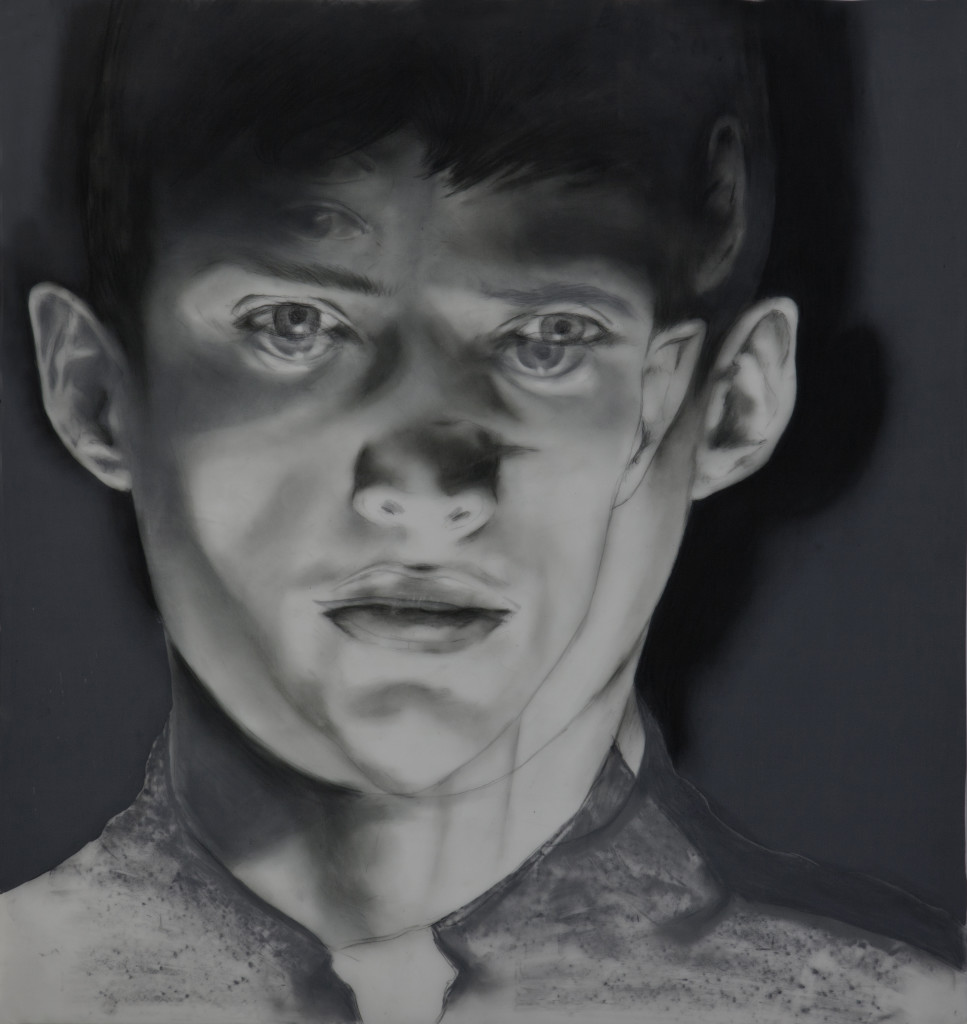

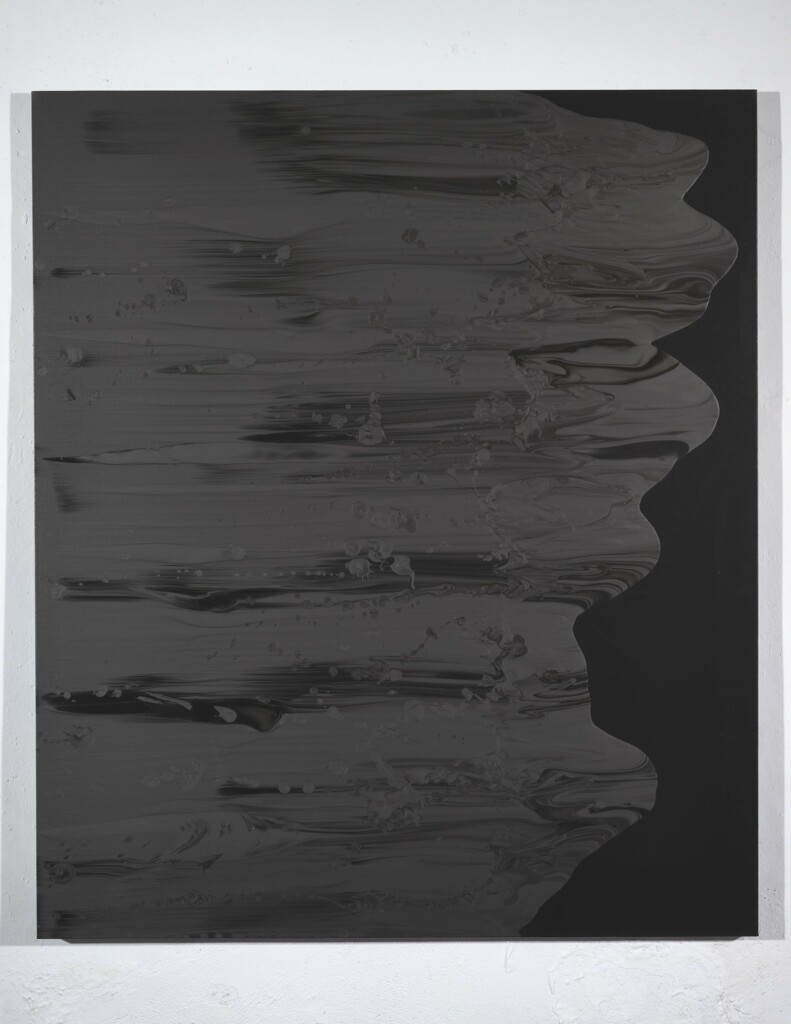

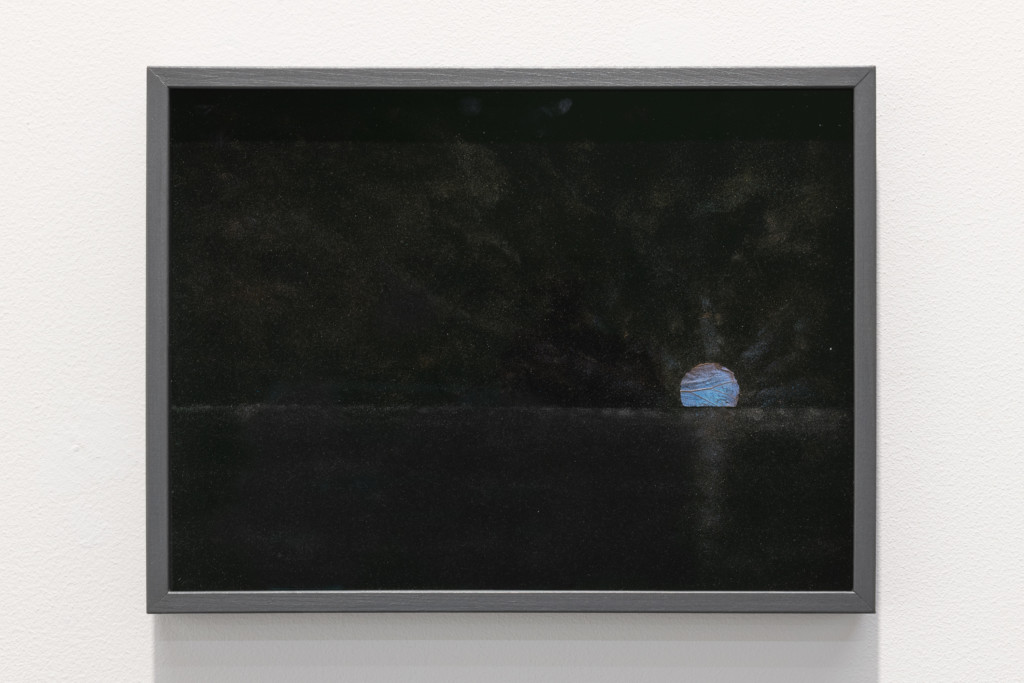

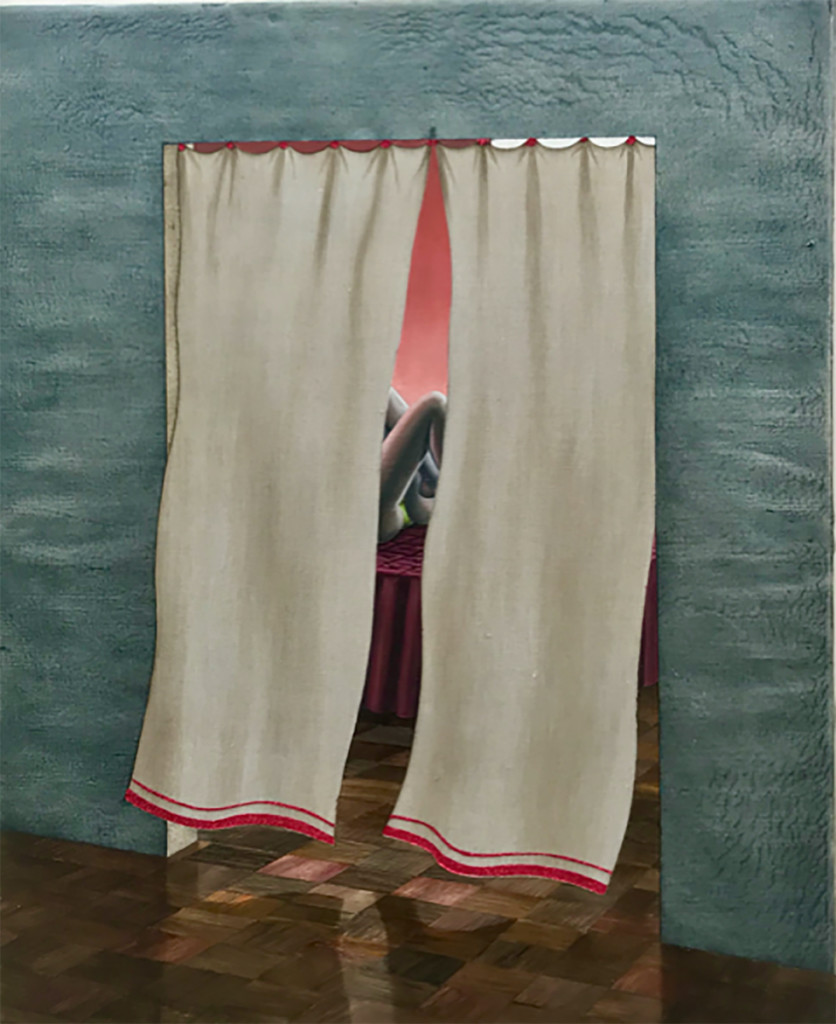

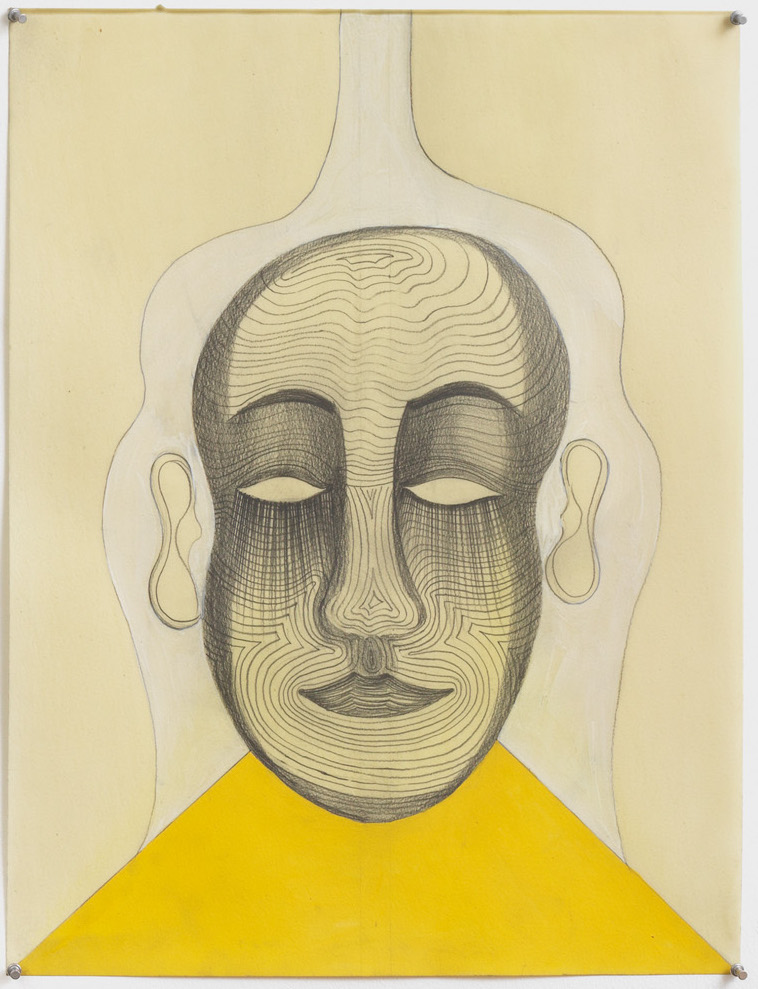

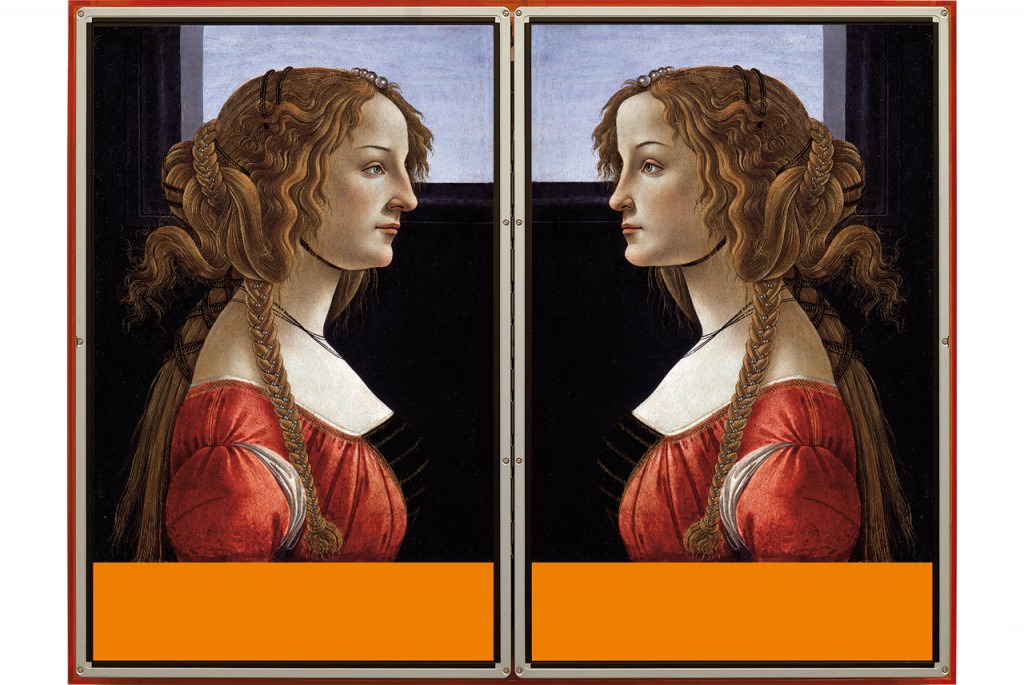

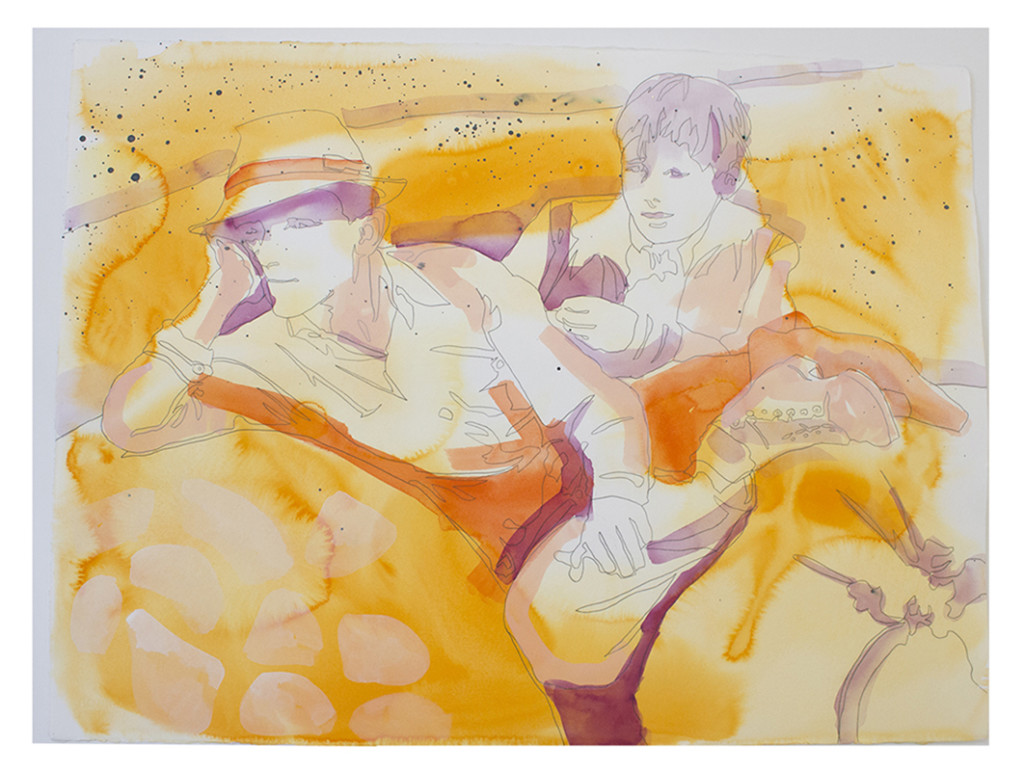

The title of the present exhibition Let Us Now Praise Famous Men refers to the book of the same name written by James Agee and illustrated with photographs by Walker Evans. Published in 1941, it documented rural life in the United States during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Francis Ruyter uses appropriationism as a tool; all the paintings have as reference photographs of the huge patrimony treasured by the Library of Congress of the United States. It is one of the largest archives in the world created from the funds of the Farm Secure Administration and the Office of War Information: black and white images that portray the life of the Americans between 1935 and 1944. These images, produced through gubernamental agencies, transcend the propaganda and, at the end, have become a reference for the American identity. It is a file reviewed by multiple authors with a generative character as it is digitized and disseminated.

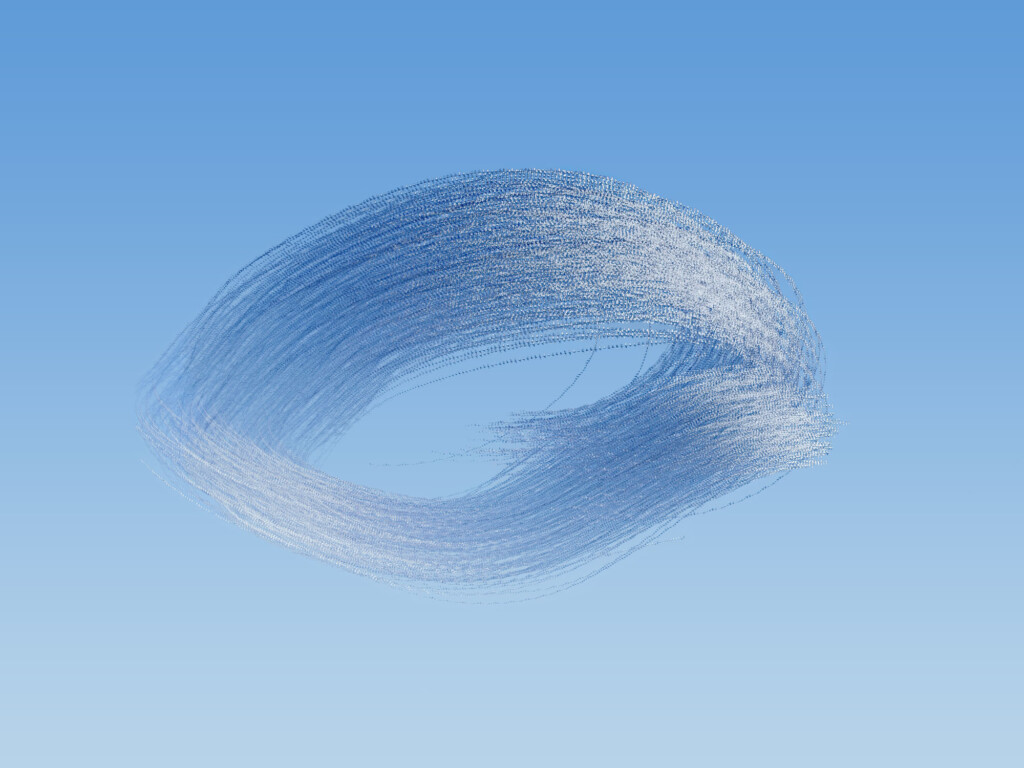

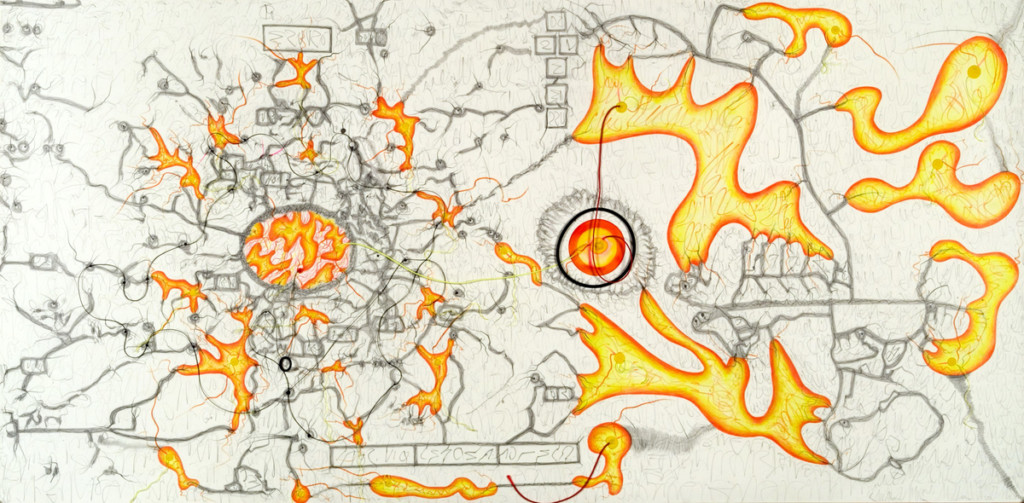

The archival objects of the post-industrial era have already been subjected to systems of order and reclassification and lately they are divided in a global scheme through the Internet. The growing presence of data banks, image files and visual interfaces allow us to trace Ruyter’s interest in photographic archives. This can be compare with technological ruins that face the changes of the scientific and social knowledge that provides Ruyter’s paintings a contextual depth of referents connected by interrelated nodes.

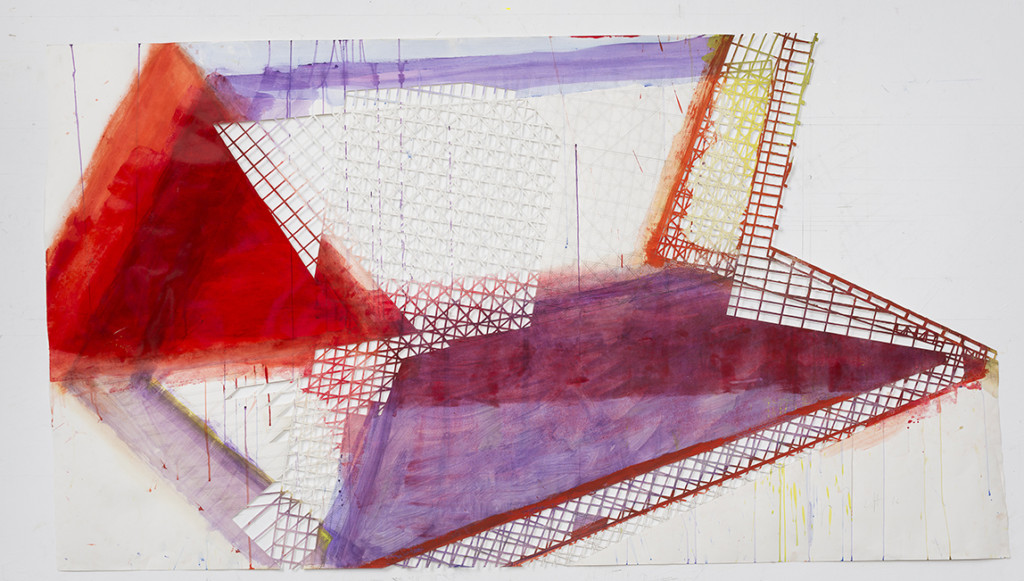

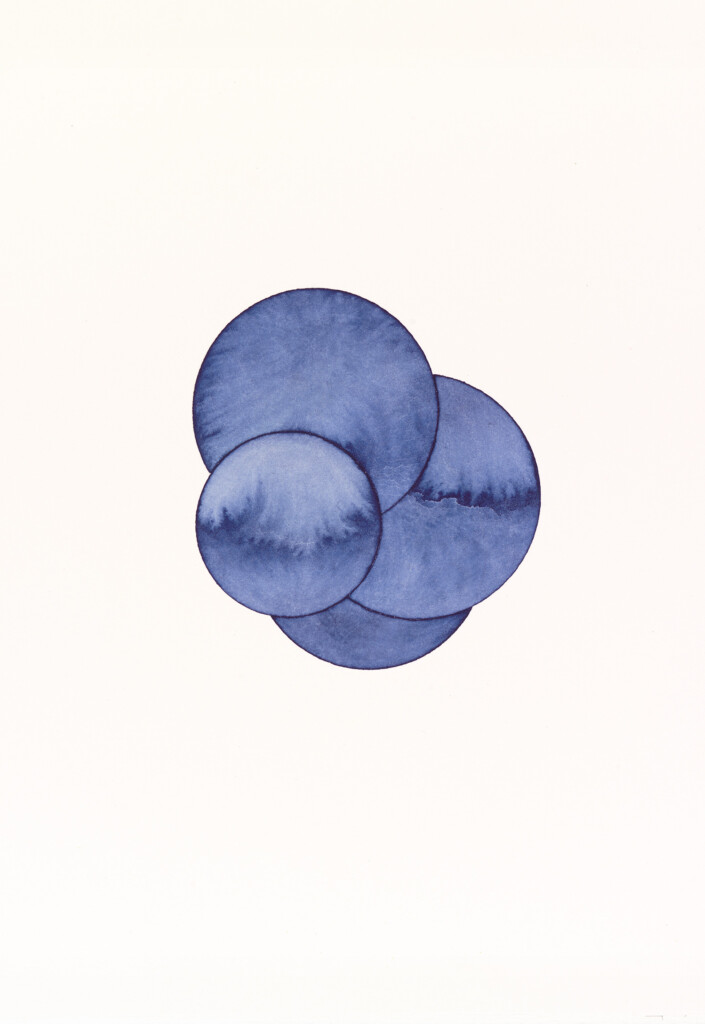

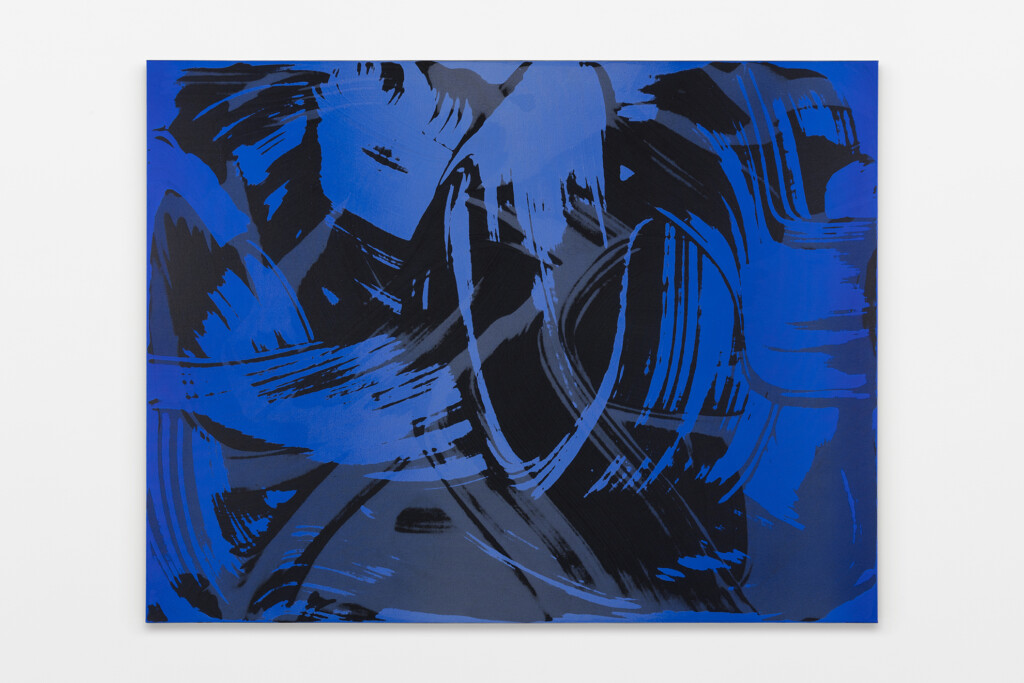

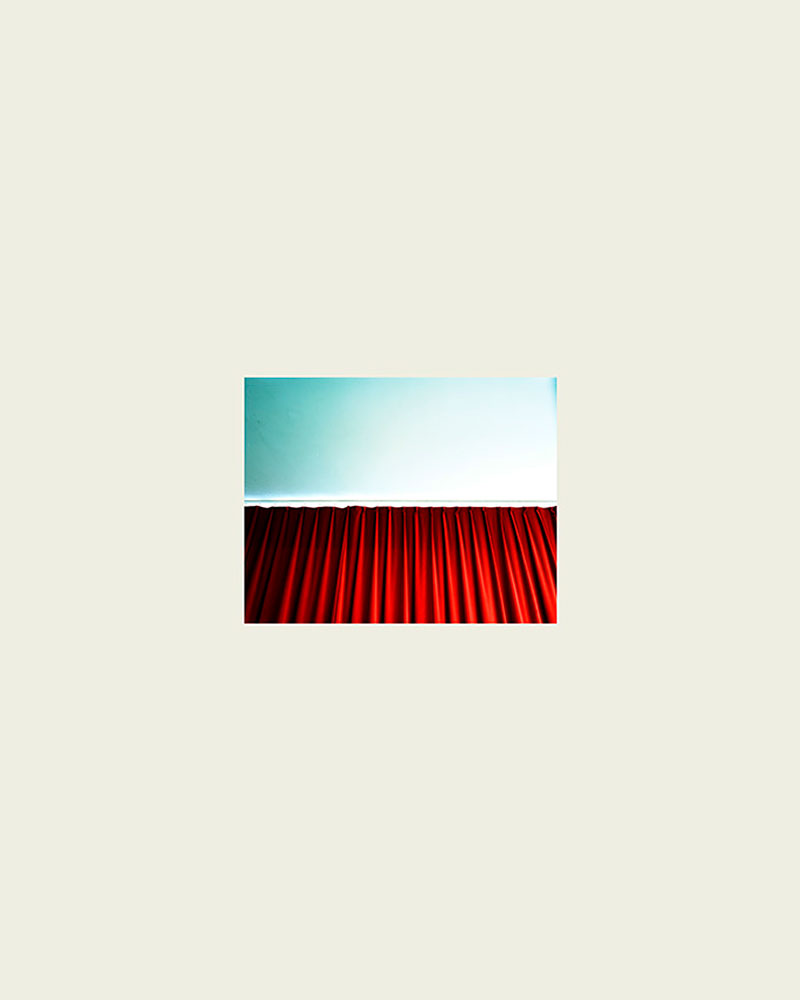

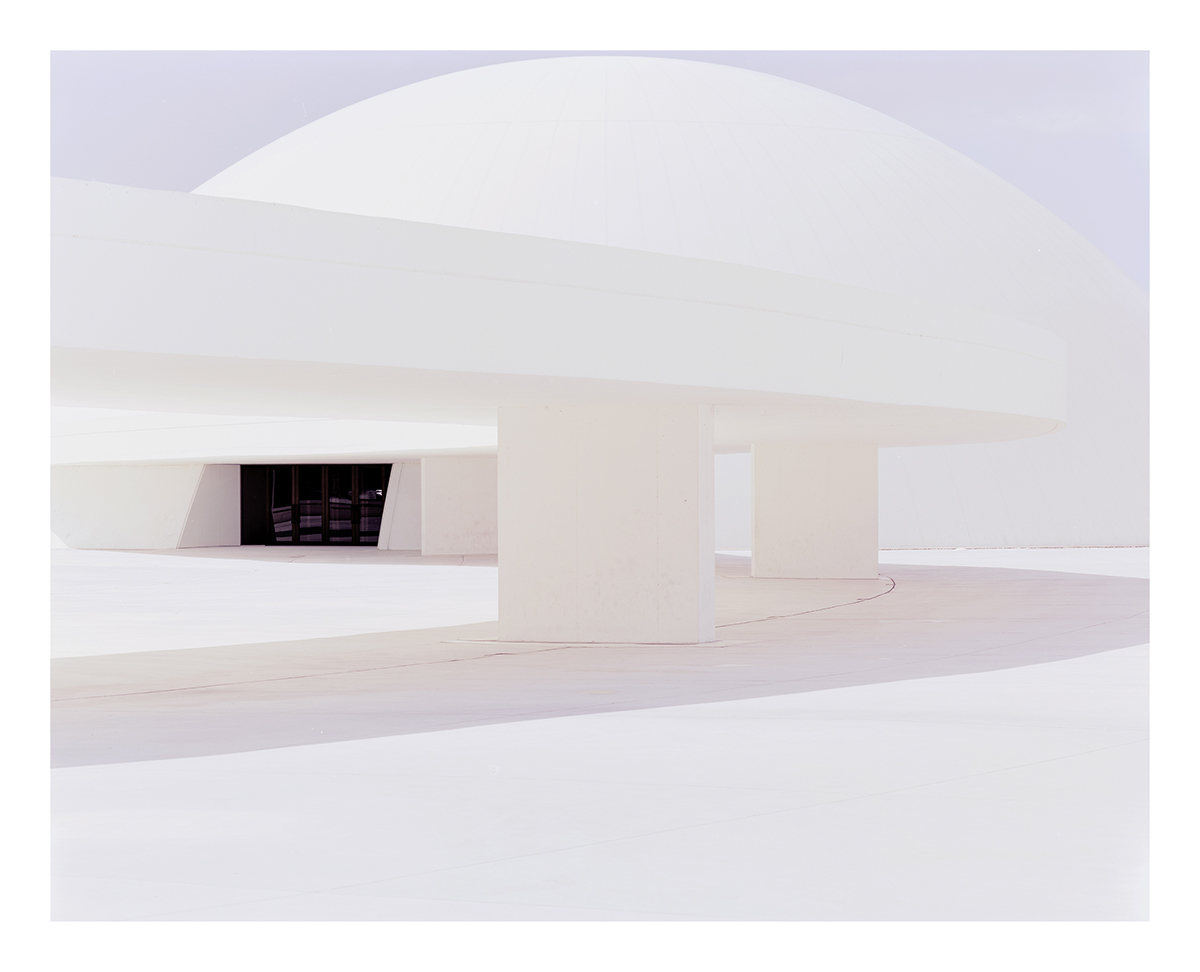

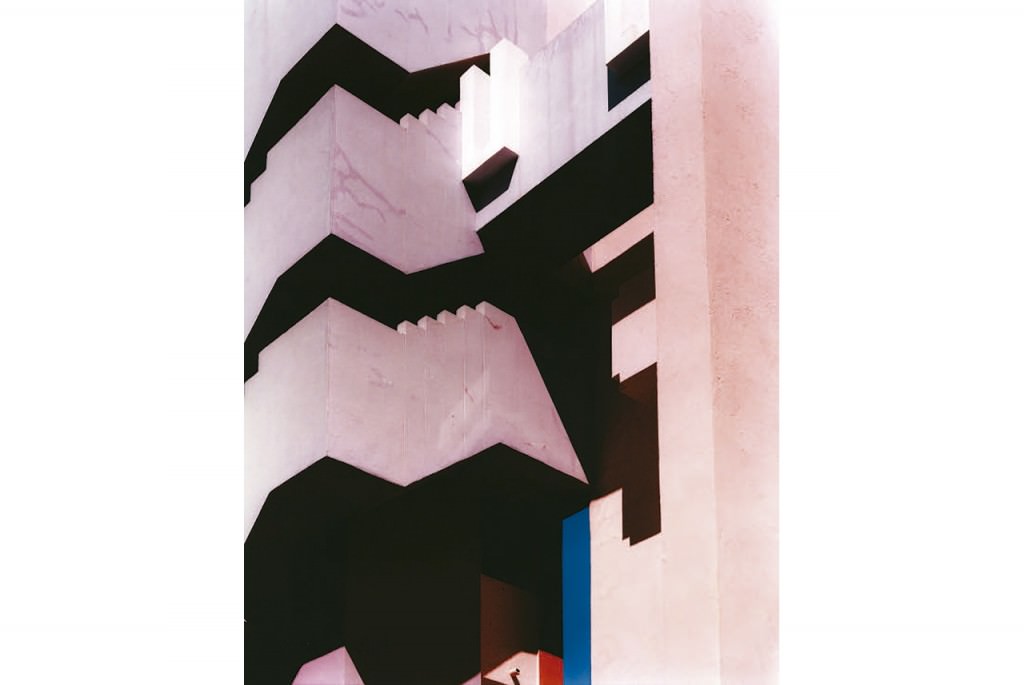

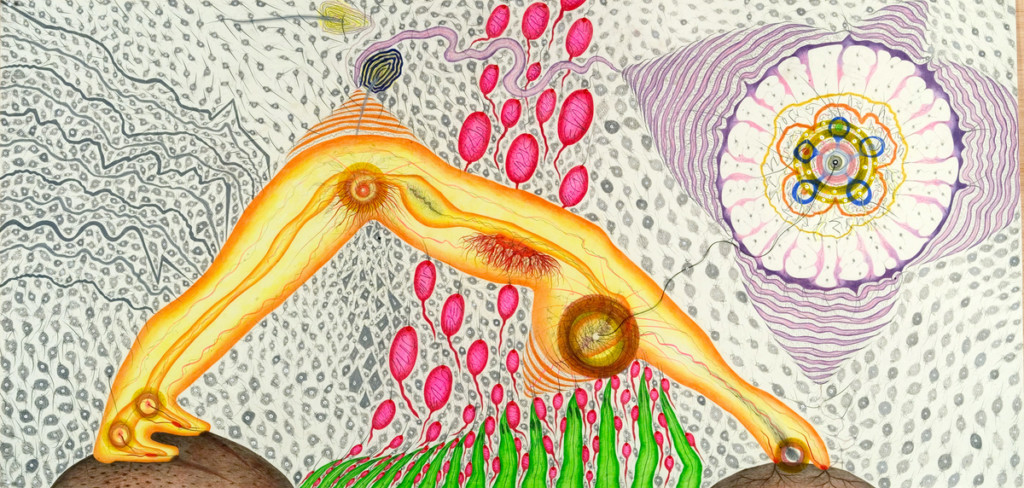

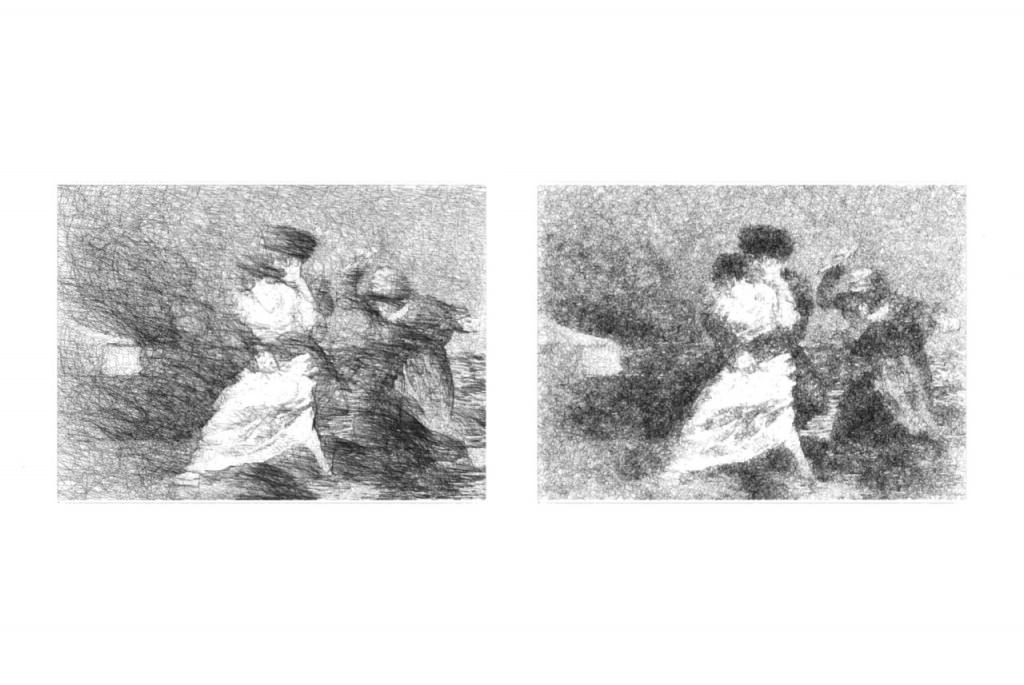

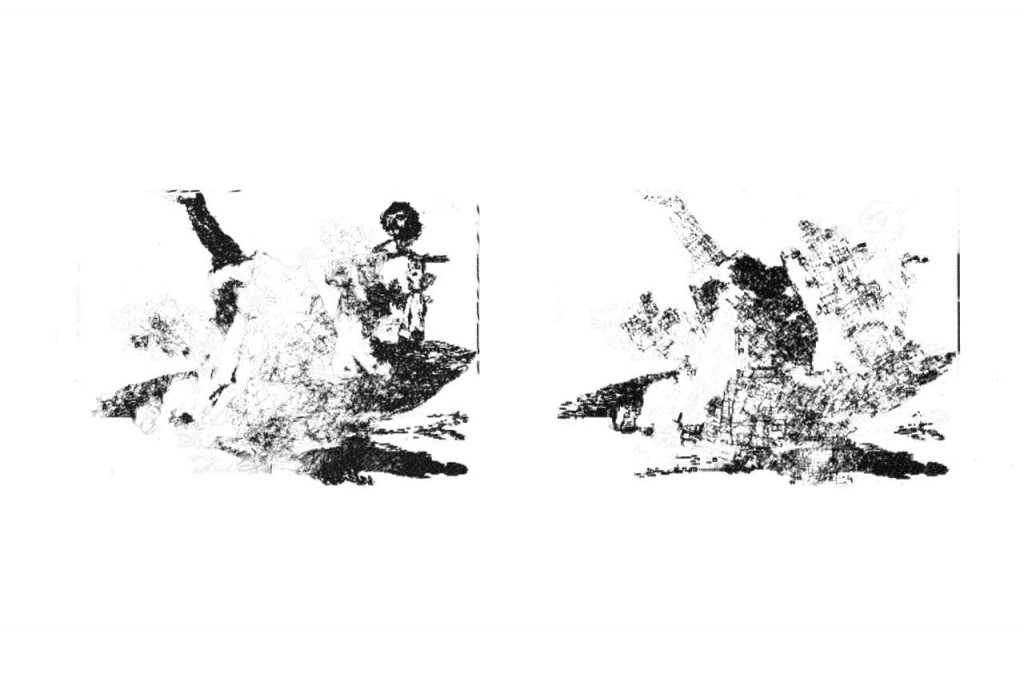

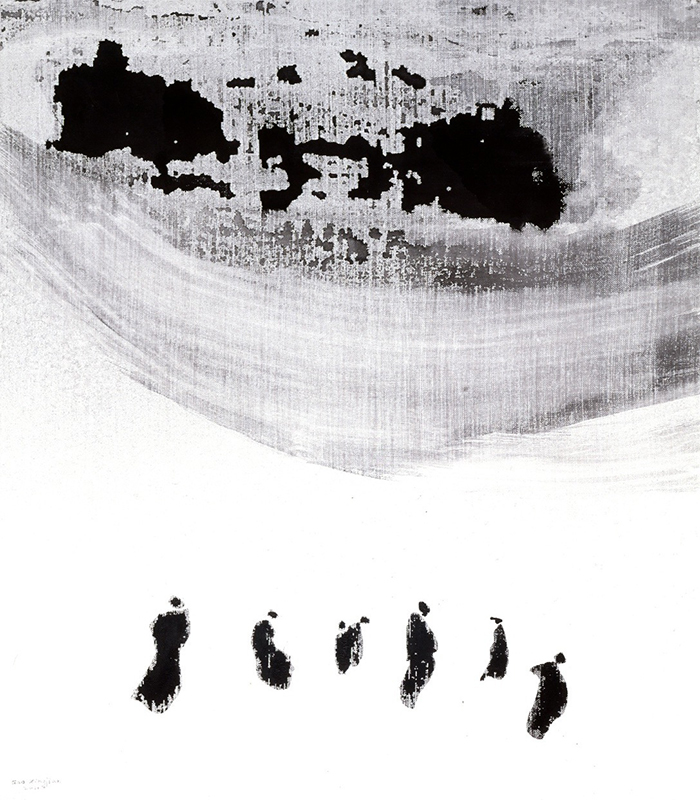

The artistic process of Francis Ruyter merges new technologies with traditional techniques of drawing and painting. Ruyter uses monochrome paint and permanent marker to recreate the images of these photographs. These works deployed visually as abstract paintings despite their figurative origin. We are faced with synthetic works with a marked tone reduction, painted with non-naturalistic colours at all, and composed of energetic colour planes. This saturated chromaticism comes violent in conflict with our perception of the photographic act as a graphic document that brings verisimilitude to the image. The contours divide the surface into planes of shadows clueless in a representation in which the illusion of depth is eliminated. This denial of the volume reduces to the minimum expression the photographic origin of the image as the language of light and emphasizes the markedly two-dimensional character of the work.